Suburban Growth and the Railroads

The New York & Harlem was the first railroad to cross into Westchester County, reaching White Plains in 1844. In 1848, the New York & New Haven opened their line along Long Island Sound. The Hudson River Railroad constructed their mainline south along the river shore and reached New York in 1851. After the end of the Civil War, proposals for new railroads reached a fever pitch. As New York City continued to expand northward, many proposals were made to link The Bronx with Westchester County, hoping to capitalize on increasing real estate values. The New York, Westchester & Boston Railroad was incorporated in March 1872 to construct a railroad from a terminal on the Harlem River in The Bronx to White Plains, along with a branch to Port Chester. The Panic of 1873 halted all progress and the company went into receivership in 1875.

The project lay dormant for twenty five years until a group of investors formed the New York City & Westchester in 1900. They discovered the old 1872 NYW&B charter, and in 1904 reorganized as the New York, Westchester & Boston Railway. Around the same time, the New York & Portchester was incorporated in 1901 to construct a four-track electric rapid transit line from The Bronx to Port Chester. Their routes along the Sound Shore sometimes only varied by a few hundred feet, and were in direct competition with the New Haven.

While both projects were able to raise large amounts of money, most of the funds went towards fighting each other in court. Both companies also faced difficulty in acquiring the necessary franchises for construction. Some cursory construction was started to satisfy legal requirements; the NYW&B began building bridge abutments in The Bronx in 1905, and the NY&P built a concrete bridge in Harrison in 1906.

“No one could explain why the New Haven had spent nearly $11 million to acquire two seemingly worthless ventures, and now was about to spend even more to construct a railroad that would compete for business in its own territory.”

In 1903, financier J.P. Morgan took control of the New Haven and installed Charles Mellen as president. Morgan took an interest in the two competing Westchester projects. By 1906, the NYW&B and the NY&P were hopelessly entangled in legal battles, and were quickly running out of money. Two bankers by the name of Marsden J. Perry and Oakleigh Thorne announced they had taken over the NYW&B, and proceeded to buy up the remaining NY&P stock. In 1907, Perry and Thorne set up the Millbrook Company to manage and control both entities.

Shortly after the Panic of 1907, all assets of the Millbrook Company were conveniently transferred to the New Haven. With the New Haven now in control, it was assumed that the project would die a quick death. In a surprising turn of events, Mellen announced the New Haven would pursue completion of the Westchester project. No one could explain why the New Haven had spent nearly $11 million to acquire two seemingly worthless ventures, and now was about to spend even more to construct a railroad that would compete for business in its own territory. At the end of 1909, the NYW&B and the NY&P were merged, with approval coming from the New York State Public Service Commission in 1910.

The New Haven Steps In

Under New Haven control, the new New York, Westchester & Boston Railroad went through many changes from its original plan. Because the original NYW&B had already spent a considerable amount on real estate and construction, they chose to use its franchise, though somewhat modified. With recent success in electrifying its mainline, it was decided that the NYW&B would also be all-electric. Two additional tracks for the Westchester were built along the Harlem River Branch from West Farms to the New Haven’s existing Harlem River passenger terminal.

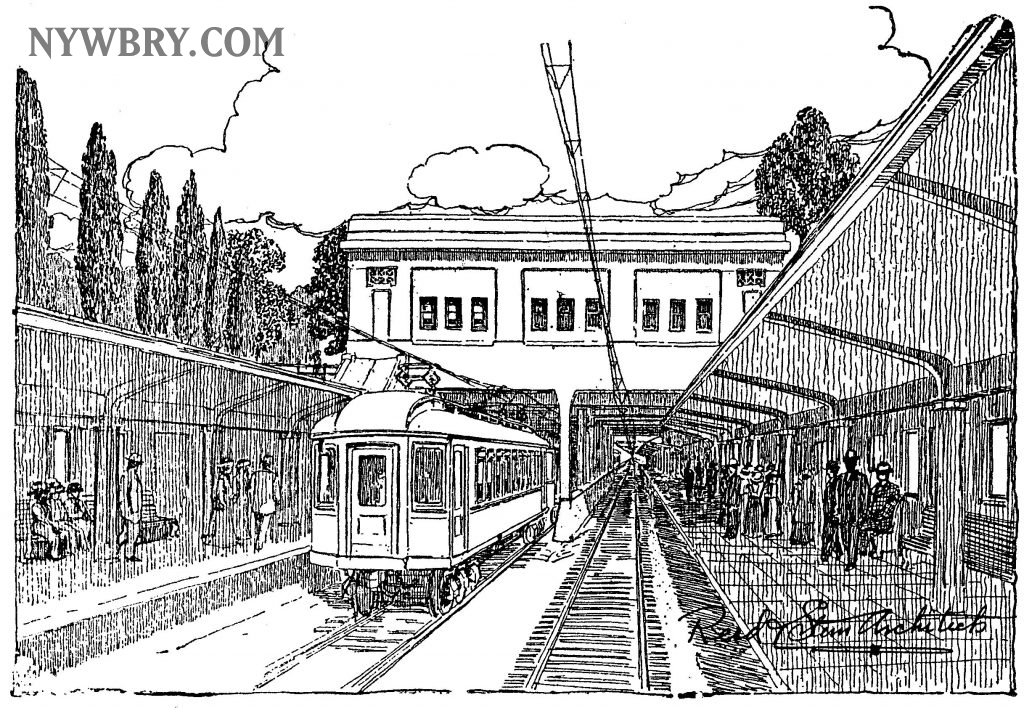

The next two years saw the most magnificent railroad property ever constructed suddenly appear on the landscape of Westchester County. Banking that the city would continue to grow northward, and that large populations would be moving to the suburbs, the NYW&B stood ready to serve them. It can be argued that the facilities were the most attractive built new for any railroad of the time. Modern electric multiple-unit passenger coaches were ordered from Pressed Steel Car Company, based on an innovative design by electrical engineer L.B. Stillwell. The coaches featured an additional center door, to facilitate quicker passenger boarding.

Modern electric multiple-unit passenger coaches were ordered from Pressed Steel Car Co., based on an innovative design by electrical engineer L.B. Stillwell.

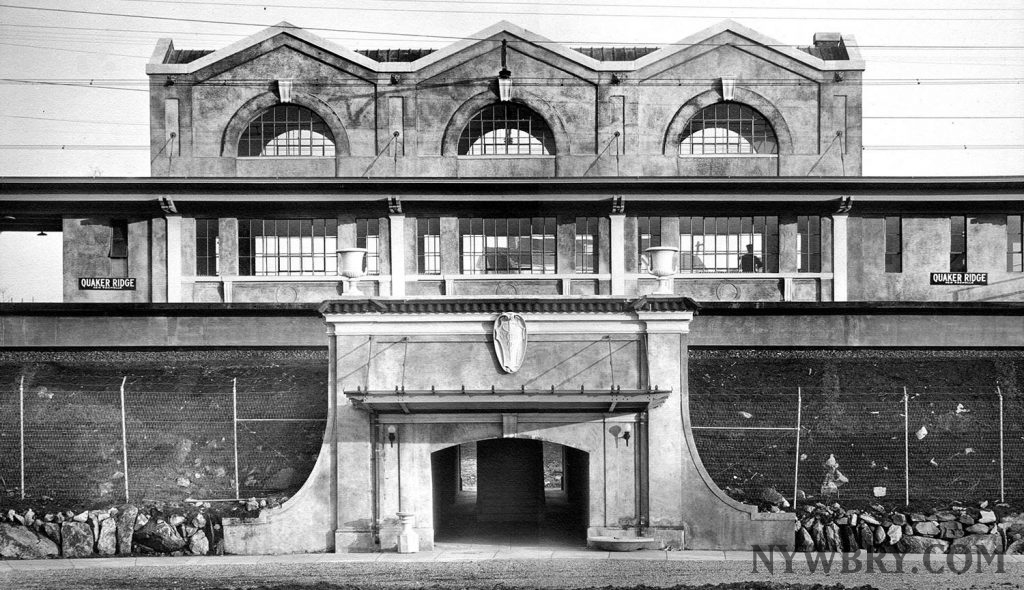

Stations were styled after Classical, simplified Mission, and Italianante architectural forms. High-level platforms allowed passengers to quickly enter and exit the trains. With exterior finishes of smooth concrete and terra cotta tile, the interiors featured gleaming marble and vaulted ceilings. Even the interlocking towers were finished in a manner that suggested an attention to detail never seen before. There were no grade crossings on the Westchester, which necessitated the construction of many bridges and viaducts.

Improvements were also made to the Harlem River Branch, which the Westchester shared with the New Haven from West Farms Junction to Harlem River. New and improved passenger stations were built along the branch from New Rochelle to the terminal at Harlem River. Both the NYW&B and the New Haven were preparing for a dramatic surge in passenger traffic.

The Westchester’s president Leverett Miller explained that he was under instructions from J.P. Morgan to build the finest suburban railway that could be built…

Architect Alfred Fellheimer (also involved in the Grand Central Terminal project) argued that railroads don’t just spring up fully grown, they usually take years to develop and improve their facilities. The Westchester’s president Leverett Miller explained that he was under instructions from J.P. Morgan to build the finest suburban railway that could be built. And so it went that the New Haven reported in 1912 that total construction costs (including acquiring rolling stock) amounted to $22 million (equal to approximately $475 million in 2007). However, the New Haven reported spending more than $36 million, leaving another $14 million unaccounted for. By the time the ICC opened an investigation on the matter in 1914, J.P. Morgan had already died, and former New Haven president Mellen could not shed any light on the matter either. The original construction cost accounts for the origin of the Westchester’s “Million-Dollar-A-Mile” nickname.

The NYW&B opened for service in May 29, 1912. Even though construction crews rushed to finish the work, not all the facilities were completed in time for opening day. The large East 180th Street station was not ready in time, so trains left from a temporary arrangement at Adams Street until the grand depot opened. The White Plains terminal was not ready either, so trains terminated at Mamaroneck Avenue until July. Full service to Harlem River began in August. Fifteen more cars were added to the roster in 1914 to accommodate growing business.

Traffic picked up when new subway connections were established at East 180th Street in 1917, and at Hunt’s Point in 1919. The Harlem River terminal connected with the Second Avenue Elevated, and an improved connection and rebuilt station opened in 1924. Inexpensive fares coaxed more riders onto the Westchester’s efficient trains and business continued to improve, though the railroad had yet to show a profit.

The Westchester Northern Project

Looking to expand beyond their initial 20-mile route, a northward extension from White Plains was considered. Shortly after taking control of the NYW&B in 1909, an ambitious extension was planned from White Plains to Brewster and Danbury, opening up the eastern part of rural Westchester County. The Westchester Northern Railroad was chartered in 1910, with the possible hope of offering a high-speed cut-off route for freight trains coming from Maybrook via the Poughkeepsie Bridge, and for freight and passenger trains coming from Pittsfield via the Berkshire Division. The true motivations for this extension have yet to be discovered.

The Millbrook Company was actively engaged in purchasing real estate all along the route. The board of directors approved construction in 1912, yet little was accomplished. In 1913, J.P. Morgan died, and with him went the aggressive support for any expansion. The WN was merged into the NYW&B in 1915, and the project was officially cancelled in 1925.

The Port Chester Extension

The Port Chester Branch was designed to siphon off more of the New Haven’s local commuter traffic, and bring increased revenue to the Westchester. The New Haven was looking for ways to reduce the number of trains into Grand Central Terminal, for which they paid a rental fee to the New York Central (which was figured into the cost of a ticket). The new line to Port Chester was built along the west side of the New Haven’s four-track mainline. Construction began in 1921, extending from North Avenue to Larchmont, then to Mamaroneck in 1926, Harrison in 1927, Rye in 1928 and Port Chester in 1929. For $150,000 a year, the NYW&B rented the right of way from its parent, the New Haven.

The Port Chester Branch swung sharply in and out at all of its stations, plus it had seven regular curves. Flange wear and squealling wheels were pretty much the rule along the of the right of way to Port Chester. Other characteristics were the wooden station platforms beginning at the Pine Brook stop in New Rochelle. The stations at Pine Brook and West Street were little phone booth sized ticket offices. Independent ticket offices at Port Chester and Larchmont Gardens were a far cry from their cousins on the White Plains Branch. Mamaroneck, Larchmont and Harrison were joint facilities with the New Haven, yet the Westchester maintained a separate fare control area. Building the extension turned out to be a good investment, accounting for most of the revenue in later years.

While the Westchester was able to pay an upwardly increasing portion of its expenses, it was never enough to turn a profit…

Slow, Painful Death

As the years went by, traffic on the NYW&B increased positively from 2,874,484 in 1913 to 6,283,325 in 1920. Its best year ever was 1928 with 14,053,188 riders. While the Westchester was able to pay an upwardly increasing portion of its expenses, it was never enough to turn a profit or convince the New Haven to invest further in the line. The stock market crash of 1929 marked the beginning of the Great Depression, which prevented the rapid development expected for the wealthy suburbs. The worst was yet to come. In 1930, president Miller was removed and management was assumed by John Pelley, president of the New Haven.

On October 23, 1935, the New Haven petitioned the Federal Court for bankruptcy reorganization. When the New Haven declared bankruptcy, they ceased interest payments on the Westchester’s bonds. This, in turn, forced the Westchester to declare bankruptcy nearly a month later on November 30. The NYW&B guaranteed its bonds through the Guaranty Trust Company of New York. The 1911 First Mortgage document shows $60 million worth of bonds, which were payable January 1 and July 1, 1946. The only way to wipe out $60 million in debt was to get rid of the line before the bonds were due. Since no one was in a position to purchase the company from the New Haven, this meant ceasing operations and liquidating the railroad.

A bill authorizing purchase of the railroad through a new public authority made it all the way to the legislature, only to be vetoed by Governor Herbert H. Lehman…

Just get rid of it at all costs! This seemed to be the thoughts in the minds of New Haven’s top brass. The trustees tried reducing ticket fares, which increased ridership, but didn’t help the bottom line. The Westchester owed back taxes to many of the municipalities along the line. Villages balked when the railroad asked for tax reductions, fearing other industries would seek the same relief.

In June 1937, trusteeship ended and the railroad was placed in equity receivership. Big ideas for salvation appeared in the newspapers almost every other day, but they were never acted on. The Port Chester Branch closed on October 31, 1937, and the rest of the railroad followed at the end of the year. While the tracks lay dormant, the fight did not end. A group of private investors wanted to take over the Westchester if it were possible to forgive the back taxes and rentals. The municipalities and the New Haven wanted no part of it.

A bill authorizing purchase of the railroad through a new public authority made it all the way to the legislature, only to be vetoed by Governor Herbert H. Lehman. Eventually Judge Knox signed the railroad’s death sentence and ordered the railroad scrapped in order to pay off its creditors. First to come down was the copper catenary wire in 1939. In 1940, New York City purchased the section from Dyre Avenue to 180th Street for inclusion in the new unified subway system.

Last minute proposals were advanced to operate the White Plains line as a separate railroad, with service running over the center express tracks from Kingsbridge Road to East 180th Street. Catenary supports remained for the opening day of subway service on The Bronx portion while the proposal was prepared. Unfortunately, there was little support for the idea, and the death knell sounded for the Westchester.

Many of the stations… were given to the towns as payment for back taxes. The towns had no use for them as they were left to decay, a sad reminder of what once was…

Epilogue

The property was auctioned by the government in March 1942, and fetched only $423,000 for the remainder of the once proud railroad. The war effort encouraged the rapid salvage of the NYW&B’s catenary supports, bridges, and viaducts. The New Haven reclaimed the Stillwell cars they leased to the Westchester, and converted them into locomotive-hauled coaches at their Readville shops. Some of the other cars were used in transporting war workers around the California oil fields.

The remainder of the cars were sold off and eventually scrapped. As of this writing, one sole coach exists in Peru, though its current status is unknown. The Westchester’s Westinghouse electric freight locomotive went to the New Haven and became their 0224. Many of the stations along the right of way were given to the towns as payment for back taxes. The towns had no use for them and they were left to decay, a sad reminder of what once was.

Only a handful of stations remain in Westchester today, including Quaker Ridge, Heathcote, Wykagyl, East Third Street, Larchmont Gardens and Port Chester. The ruins of Columbus Avenue station can be seen from passing Metro-North trains on the New Haven Line. Motorists on the Hutchinson River Parkway might notice one of the abutments for the great steel viaduct that once spanned the valley.

The Bronx portion of the line would fare a little better than the rest of the system. In 1940, the City of New York purchased the segment from East 180th Street to Dyre Avenue and incorporated it into the subway system, adding a much needed service to the East Bronx. Today, trains from the IRT No. 5 line continue to serve East 180th Street, Morris Park, Pelham Parkway, Gun Hill Road, Baychester Avenue and Dyre Avenue. The long viaduct that led to West Farms remained intact, maintaining a connection to the New Haven (and later Penn Central) for movement of rapid transit equipment on and off the subway system. The connection was severed in the late 1970s, and the viaduct was removed in parts through the 1990s.

Stations along the Harlem River Branch closed with the end of NYW&B service in 1937, and have been left to crumble in the elements. Hunts Point station was converted to retail many years ago. The venerable Harlem River offices that were visible from the Willis Avenue Bridge for so many years finally succumbed to the wrecking ball in 2006. East Third Street station in Mount Vernon was torn down in 2016. Traces of The Westchester outside the Bronx are getting harder to find, but the memories will live on.

—By Robert A. Bang and Otto M. Vondrak, with thanks to Herbert Harwood. This passage courtesy “Forgotten Railroads Through Westchester County”